Chef: Narisawa Yoshihiro Website: www.narisawa-yoshihiro.com Cuisine: French Japanese

Chef: Narisawa Yoshihiro Website: www.narisawa-yoshihiro.com Cuisine: French Japanese

I’ve got a confession to make. I’ve always been embarrassed by the fact that despite my Japanese heritage I’ve not had many opportunities exploring the fine dining scene in my own country. This naturally had to change and September 2014 was my opportunity (Note that the significant delay in my write-up has been due to the arrival of my first daughter in November 2014). Over the recent years I’d managed to create a long list of restaurants I planned to visit when I returned home and that included Narisawa. I was curious about its reputation for being unorthodox in a country that was deeply rooted to its tradition.

After all, wouldn’t you be curious to find out the culmination of modern French cooking techniques with fresh seasonal Japanese produce? After receiving their second Michelin star in 2010 and successfully retaining the title of best Asian restaurant in San Pellegrino’s 50 Best Awards over the past few years there was no way I could pass this opportunity.

After all, wouldn’t you be curious to find out the culmination of modern French cooking techniques with fresh seasonal Japanese produce? After receiving their second Michelin star in 2010 and successfully retaining the title of best Asian restaurant in San Pellegrino’s 50 Best Awards over the past few years there was no way I could pass this opportunity.

Yoshihiro Narisawa opened Les Creations de Narisawa (now known simply as Narisawa) back in 2003 on his return from Europe after training under the likes of big hitters like Frédy Girardet, Paul Bocuse and Joel Robuchon. The cuisine here was however difficult to label. It was decidedly modern and drew on French techniques yet was not tied down to one particular style of cuisine. What’s more, Narisawa departed from the traditional focus on agriculturally cultivated produce. Instead he favoured natural ingredients and produces from the wild forests and mountains like nuts, berries and the wild animals that fed on them.

Yoshihiro Narisawa opened Les Creations de Narisawa (now known simply as Narisawa) back in 2003 on his return from Europe after training under the likes of big hitters like Frédy Girardet, Paul Bocuse and Joel Robuchon. The cuisine here was however difficult to label. It was decidedly modern and drew on French techniques yet was not tied down to one particular style of cuisine. What’s more, Narisawa departed from the traditional focus on agriculturally cultivated produce. Instead he favoured natural ingredients and produces from the wild forests and mountains like nuts, berries and the wild animals that fed on them.

The theme of our tasting menu reflected the season we visited, autumn. Unlike many of the restaurants we had visited on this occasion, the front of house was well versed in English which made the meal more interactive for my non-Japanese speaking companions. We left ourselves in the capable hand of the front of house and kicked off our meal with a glass of their Vilmart et Cie, Grand Cellier, Brut, Premier Cru which had been bottled specially for the restaurant.

The theme of our tasting menu reflected the season we visited, autumn. Unlike many of the restaurants we had visited on this occasion, the front of house was well versed in English which made the meal more interactive for my non-Japanese speaking companions. We left ourselves in the capable hand of the front of house and kicked off our meal with a glass of their Vilmart et Cie, Grand Cellier, Brut, Premier Cru which had been bottled specially for the restaurant.

As we sipped on our glass of bubbles our friendly waiter prepared the Bread of the Forest 2010. The bread was proved at our table. It was made using wild yeast from the Shirakami ranges, one of the most serene and beautiful UNESCO natural heritage sites of the world located between Aomori and Akita prefecture, and was gently heated over a candle. The bread mixture contained ao-yuzu (green yuzu) and ki no me (木の芽) leaves from the Japanese Prickly Ash tree, which added a citrus scent and peppery note.

As we sipped on our glass of bubbles our friendly waiter prepared the Bread of the Forest 2010. The bread was proved at our table. It was made using wild yeast from the Shirakami ranges, one of the most serene and beautiful UNESCO natural heritage sites of the world located between Aomori and Akita prefecture, and was gently heated over a candle. The bread mixture contained ao-yuzu (green yuzu) and ki no me (木の芽) leaves from the Japanese Prickly Ash tree, which added a citrus scent and peppery note.

The dough mixture was then transferred across to a hot stone bowl to bake. The floral arrangement surrounding the bowl represented the season.

The dough mixture was then transferred across to a hot stone bowl to bake. The floral arrangement surrounding the bowl represented the season.

The wait was finally over. What a way to start the meal; an amuse bouche of the Essence of the Forest and Satoyama Scenery. It consisted of a “forest floor” of soy pulp or okara (御殻), bamboo and green tea powder and soya milk yoghurt paste. It was served with the “bark” of mountain vegetables (山菜) such as deep fried burdock skin, sourced from Ishikawa prefecture, which had been brushed with a syrup. We were instructed to eat with our hands and wash it down with…

The wait was finally over. What a way to start the meal; an amuse bouche of the Essence of the Forest and Satoyama Scenery. It consisted of a “forest floor” of soy pulp or okara (御殻), bamboo and green tea powder and soya milk yoghurt paste. It was served with the “bark” of mountain vegetables (山菜) such as deep fried burdock skin, sourced from Ishikawa prefecture, which had been brushed with a syrup. We were instructed to eat with our hands and wash it down with…

… “spring water” infused with oak and served in a cedar cup. The flavours were very clean, evoking childhood memories of hikes through moss-covered mountains in Japan. Everything worked in harmony and I felt truly depicted the essence of the Japanese forest. I particularly loved the crispy texture of the burdock root. What I found truly remarkable was that no additional seasoning had been added to this dish, nor did it need any. I could see why this dish had stayed on their menu for over five years.

… “spring water” infused with oak and served in a cedar cup. The flavours were very clean, evoking childhood memories of hikes through moss-covered mountains in Japan. Everything worked in harmony and I felt truly depicted the essence of the Japanese forest. I particularly loved the crispy texture of the burdock root. What I found truly remarkable was that no additional seasoning had been added to this dish, nor did it need any. I could see why this dish had stayed on their menu for over five years.

Our second amuse bouche of Sumi (炭) was essentially braised onion coated in a mixture of charcoal and leek powder. It had been deep fried and served on a magnolia leaf. The sweetness of the onion was an unexpected surprise.

Our second amuse bouche of Sumi (炭) was essentially braised onion coated in a mixture of charcoal and leek powder. It had been deep fried and served on a magnolia leaf. The sweetness of the onion was an unexpected surprise.

Our bread was finally ready after 12 minutes of baking and was served to us with chestnut tree powder. I had no particular expectation for the bread as I had assumed this was predominantly to provide theater to the meal. I was, however, mistaken. Whilst it wasn’t the best bread I’d ever eaten, it had all the hallmarks of a good bread. It was soft, fluffy and warm. What’s more, the yuzu added an inviting scent yet remained subtle on the palate.

The last installment of the amuse bouche was Okinawa. A dried sea-snake was presented in the middle of the table whilst the waiter explained the dish.

The last installment of the amuse bouche was Okinawa. A dried sea-snake was presented in the middle of the table whilst the waiter explained the dish.

All the ingredients were sourced from Okinawa. The most important component of this dish was the broth that was made over six hours of using a bonito flake dashi, dried and smoked sea-snake and pork from Kagoshima. A slither of crunchy winter melon, taimo (a sticky Okinawa variety of taro which is normally used for dessert) and a crispy pork skin was added to complete the dish. The broth had a great depth of flavour and the textural contrast of each element worked very well. A deceivingly simple looking dish that worked very well with a glass of the 1981 Chateau Gen Brown Rice Sake, Mie, Japan.

All the ingredients were sourced from Okinawa. The most important component of this dish was the broth that was made over six hours of using a bonito flake dashi, dried and smoked sea-snake and pork from Kagoshima. A slither of crunchy winter melon, taimo (a sticky Okinawa variety of taro which is normally used for dessert) and a crispy pork skin was added to complete the dish. The broth had a great depth of flavour and the textural contrast of each element worked very well. A deceivingly simple looking dish that worked very well with a glass of the 1981 Chateau Gen Brown Rice Sake, Mie, Japan.

A Moss butter made from dehydrated black olives, chlorophyll and Hokkaido butter was presented prior to the next course. It tasted how it looked – mossy! Not that it was a bad thing but certainly different to anything I’ve tried before.

A Moss butter made from dehydrated black olives, chlorophyll and Hokkaido butter was presented prior to the next course. It tasted how it looked – mossy! Not that it was a bad thing but certainly different to anything I’ve tried before.

The Uni Sea Urchin, amaebi, yuzu was another example of a perfectly balanced dish. The amaebi (spot prawn) and sea urchin sourced from Mikawa, Aichi prefecture, was very creamy and sweet. The katsuodashi jelly (set and infused for six hours) gave depth to the dish and the yuzu and tomato hiding underneath cut through the rich flavour, leaving only a fragrant aftertaste. I could also sense a slight peppery heat that contrasted against the cold dish. Beautiful. The dish was matched with a glass of the 2012 Chateau Lestille, Entre Deux Mers, Bordeaux.

The Uni Sea Urchin, amaebi, yuzu was another example of a perfectly balanced dish. The amaebi (spot prawn) and sea urchin sourced from Mikawa, Aichi prefecture, was very creamy and sweet. The katsuodashi jelly (set and infused for six hours) gave depth to the dish and the yuzu and tomato hiding underneath cut through the rich flavour, leaving only a fragrant aftertaste. I could also sense a slight peppery heat that contrasted against the cold dish. Beautiful. The dish was matched with a glass of the 2012 Chateau Lestille, Entre Deux Mers, Bordeaux.

The crustacean course of the day was the Langoustine, garden. Under the “garden”, created from a variety of greens and flowers that had been foraged early that morning, lay…

The crustacean course of the day was the Langoustine, garden. Under the “garden”, created from a variety of greens and flowers that had been foraged early that morning, lay…

… a juicy Japanese langoustine (Akazaebi) from Suruga Bay. It had been very lightly seared and served as a warm sashimi. The creamy langoustine was cooked perfectly and the scallop jus served over the dish intensified the crustacean flavour. The only issue I had was with the portion size. I wanted more… The matching 2009 Chassagne Montrachet Les Caillerets, Bourgogne, France was a perfect match with its buttery flavour.

… a juicy Japanese langoustine (Akazaebi) from Suruga Bay. It had been very lightly seared and served as a warm sashimi. The creamy langoustine was cooked perfectly and the scallop jus served over the dish intensified the crustacean flavour. The only issue I had was with the portion size. I wanted more… The matching 2009 Chassagne Montrachet Les Caillerets, Bourgogne, France was a perfect match with its buttery flavour.

The next course was a Pigeon which represented the animals that fed from the forest. The pigeon was basted at a constant temperature of 57 degrees celsius to ensure a pink finish. It was accompanied with charred beetroot and wild berries also foraged from the forest. The plump pigeon was cooked perfectly with a beautiful texture. I particularly loved the reduced salumi sauce that seasoned the dish. Exquisite! The accompanying wine was a rather smoky and oaky 2001 Lynsolence, Saint-Emilion, Bordeaux. Only 20 cases had been imported into Japan. What a treat!

The next course was a Pigeon which represented the animals that fed from the forest. The pigeon was basted at a constant temperature of 57 degrees celsius to ensure a pink finish. It was accompanied with charred beetroot and wild berries also foraged from the forest. The plump pigeon was cooked perfectly with a beautiful texture. I particularly loved the reduced salumi sauce that seasoned the dish. Exquisite! The accompanying wine was a rather smoky and oaky 2001 Lynsolence, Saint-Emilion, Bordeaux. Only 20 cases had been imported into Japan. What a treat!

The Kamo nasu was truly a celebration of the native Kyoto variety of aubergine. This vibrant dish consisted of a bed of soft sautéed aubergine, topped with an aubergine purée and pickles. The shiitake mushroom provided a meaty texture whilst the sheet of acidic tomato jelly and cleverly hidden shiso leaves inside cut through the oiliness of the dish. A special dish like this required a rather special glass of a 1977 Toriivilla Imamura Koshu, Yamanashi, Japan which was not too dissimilar to that of a dry sherry. It was very dry and nutty with a hint of honey and lemon. I had never heard of this Japanese winery and was even more surprised to hear they have been around for over 150 years. I knew the Japanese made a small batch of great wines but this was the first time I had come across so many.

The Kamo nasu was truly a celebration of the native Kyoto variety of aubergine. This vibrant dish consisted of a bed of soft sautéed aubergine, topped with an aubergine purée and pickles. The shiitake mushroom provided a meaty texture whilst the sheet of acidic tomato jelly and cleverly hidden shiso leaves inside cut through the oiliness of the dish. A special dish like this required a rather special glass of a 1977 Toriivilla Imamura Koshu, Yamanashi, Japan which was not too dissimilar to that of a dry sherry. It was very dry and nutty with a hint of honey and lemon. I had never heard of this Japanese winery and was even more surprised to hear they have been around for over 150 years. I knew the Japanese made a small batch of great wines but this was the first time I had come across so many.

We had a fair share of Hamo (conger pike) on our trip and the one at Narisawa was one of the best ones. The Conger pike, white peach, string bean had a lovely sweet, sour and salty undertone driven by the creamy su-miso (white miso vinegar) and kabosu foam, a citrus related to the yuzu family. The hamo, which is traditionally prepared through the fine art of honegiri (a technique that requires years of practice to efficiently break the vast number of small bones in the fish without damaging the skin), instead had, against convention, removed painstakingly each bone, one by one, by hand. I did not envy the chef but it was definitely worth the effort! Matching the dish was a glass of Shizen no manma unfiltered and undiluted sake, Terada Hoke sake brewery, Chiba.

We had a fair share of Hamo (conger pike) on our trip and the one at Narisawa was one of the best ones. The Conger pike, white peach, string bean had a lovely sweet, sour and salty undertone driven by the creamy su-miso (white miso vinegar) and kabosu foam, a citrus related to the yuzu family. The hamo, which is traditionally prepared through the fine art of honegiri (a technique that requires years of practice to efficiently break the vast number of small bones in the fish without damaging the skin), instead had, against convention, removed painstakingly each bone, one by one, by hand. I did not envy the chef but it was definitely worth the effort! Matching the dish was a glass of Shizen no manma unfiltered and undiluted sake, Terada Hoke sake brewery, Chiba.

The next seafood course, the Rosy seabass, matsutake mushroom, was presented in a what was described as a “sustainable wrap” which was supposedly environmentally friendly (admittedly I wasn’t sure how). The waiter proceeded to cut the bag…

The next seafood course, the Rosy seabass, matsutake mushroom, was presented in a what was described as a “sustainable wrap” which was supposedly environmentally friendly (admittedly I wasn’t sure how). The waiter proceeded to cut the bag…

… and the delicious earthy smell of the matsutake mushroom immediately hit the olfactory senses. The contents had been cooked in a rich duck essence for eight minutes at 180 degrees celsius which enhanced the flavours of the fatty fish. It was served with another delicious sake of 5 years aged, unfiltered and unpasteurised junmai daiginjo, Chikurin Taoyaka, Marumoto Sake Brewery, Okayama. The aka musu (rosy seabass), known for it’s similarity in fattiness to the o-toro was beautiful cooked with a raw texture and was definitely one of the best preparations I’ve ever tasted.

… and the delicious earthy smell of the matsutake mushroom immediately hit the olfactory senses. The contents had been cooked in a rich duck essence for eight minutes at 180 degrees celsius which enhanced the flavours of the fatty fish. It was served with another delicious sake of 5 years aged, unfiltered and unpasteurised junmai daiginjo, Chikurin Taoyaka, Marumoto Sake Brewery, Okayama. The aka musu (rosy seabass), known for it’s similarity in fattiness to the o-toro was beautiful cooked with a raw texture and was definitely one of the best preparations I’ve ever tasted.

For the next course a rump cut was used for the Kagoshima beef, beef essence, ichiban dashi. The ichiban dashi made from a matured konbu dashi was added to an essence of beef broth and complemented the tender lean meat, providing the umami. I particularly loved the ginnan (ginko nuts) with their nutty sweet-sour flavour that subtly reminded me of the autumn season. Accompanying the dish was a rather lovely 1994 Alain Verdet Bourgogne Hautes Côtes de Nuits, Bourgogne.

For the next course a rump cut was used for the Kagoshima beef, beef essence, ichiban dashi. The ichiban dashi made from a matured konbu dashi was added to an essence of beef broth and complemented the tender lean meat, providing the umami. I particularly loved the ginnan (ginko nuts) with their nutty sweet-sour flavour that subtly reminded me of the autumn season. Accompanying the dish was a rather lovely 1994 Alain Verdet Bourgogne Hautes Côtes de Nuits, Bourgogne.

Narisawa’s take on the classic champagne cocktail of the Bellini was simply divine. White peaches were in season and the chef made sure to make the most out of them. The same house champagne served at the start was poured over slices of white peaches neatly stacked over a brioche and layer of cream

Narisawa’s take on the classic champagne cocktail of the Bellini was simply divine. White peaches were in season and the chef made sure to make the most out of them. The same house champagne served at the start was poured over slices of white peaches neatly stacked over a brioche and layer of cream

The flavour of the peach was very distinct and provided a fresh fruity note. At first sight I expected it to be a very sweet dish but, contrary to what I thought, surprisingly the dish was very light and refreshing. The matching wine was a chenin blanc, 2004 Quarts de Chaume, Domaine des Baumard.

The flavour of the peach was very distinct and provided a fresh fruity note. At first sight I expected it to be a very sweet dish but, contrary to what I thought, surprisingly the dish was very light and refreshing. The matching wine was a chenin blanc, 2004 Quarts de Chaume, Domaine des Baumard.

The finale was Chocolate. It was perhaps a little disappointing given the caliber of the meal we had just experienced. The fondant, ice cream and foam incorporated the rather luxurious Domori chocolate from Italy. I found the flavour to be rather one dimensional despite the occasional bitterness of the darker chocolate contrasting against the milkier one. It was after all chocolate.

The finale was Chocolate. It was perhaps a little disappointing given the caliber of the meal we had just experienced. The fondant, ice cream and foam incorporated the rather luxurious Domori chocolate from Italy. I found the flavour to be rather one dimensional despite the occasional bitterness of the darker chocolate contrasting against the milkier one. It was after all chocolate.

The number of mignardises presented with our coffee was staggering. Starting with a piña colada macaron, cream puff, canelé, passion fruit, cheese cake tart, warabi mochi as well as nine flavours of chocolate macarons, there was plenty more which I could sadly not fit in my stomach. What was truly remarkable was the skill that went into preparing these flawless sweet treats. By no means an easy feat.

The number of mignardises presented with our coffee was staggering. Starting with a piña colada macaron, cream puff, canelé, passion fruit, cheese cake tart, warabi mochi as well as nine flavours of chocolate macarons, there was plenty more which I could sadly not fit in my stomach. What was truly remarkable was the skill that went into preparing these flawless sweet treats. By no means an easy feat.

As we looked over the kitchen we could see Chef Narisawa assessing each dish as it came to the pass. Nothing appeared to escape his focus, something that was very evident from the dishes we had just devoured over the last three hours. I could see why this place was so popular amongst those who sought after culinary excellence. Not only was the food delicious here, it was also eco-conscious and sustainable. I particularly loved the marriage of foreign techniques with ingredients typically engrained into traditional Japanese cuisine. By breaking the norms and boundaries, Narisawa was able to bring a whole new dimension to both French and Japanese cuisine. This wasn’t French or Japanese. This was “Narisawa cuisine”.

As we looked over the kitchen we could see Chef Narisawa assessing each dish as it came to the pass. Nothing appeared to escape his focus, something that was very evident from the dishes we had just devoured over the last three hours. I could see why this place was so popular amongst those who sought after culinary excellence. Not only was the food delicious here, it was also eco-conscious and sustainable. I particularly loved the marriage of foreign techniques with ingredients typically engrained into traditional Japanese cuisine. By breaking the norms and boundaries, Narisawa was able to bring a whole new dimension to both French and Japanese cuisine. This wasn’t French or Japanese. This was “Narisawa cuisine”.

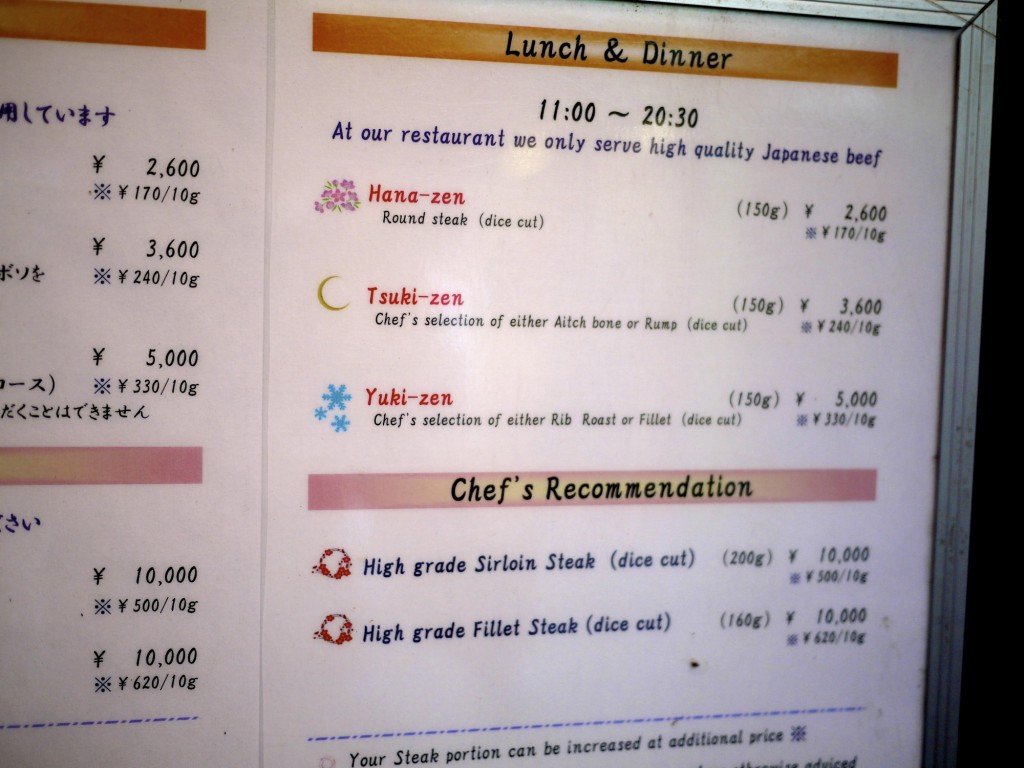

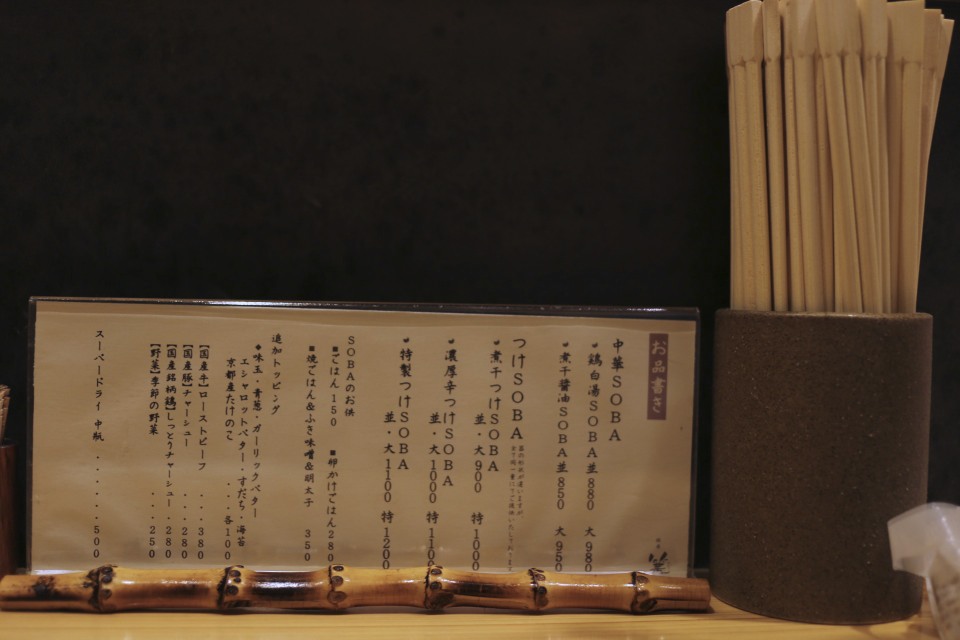

Harutaka occupies the entire third floor of the building and offers 12 counter seating and 1 private room for an additional 4 people. The restaurant is only open in the evenings and serves a standard omakase menu at approximately 30,000 yen. Unlike his mentor, his menu offers other otsumami (snacks) and comes with less attitude. Contrary to the experience I had endured the night before at Shimizu, the environment here was more relaxed. Chef Harutaka even offered an English sushi dictionary to my wife who was the only foreigner dining that evening, which was kindly received.

Harutaka occupies the entire third floor of the building and offers 12 counter seating and 1 private room for an additional 4 people. The restaurant is only open in the evenings and serves a standard omakase menu at approximately 30,000 yen. Unlike his mentor, his menu offers other otsumami (snacks) and comes with less attitude. Contrary to the experience I had endured the night before at Shimizu, the environment here was more relaxed. Chef Harutaka even offered an English sushi dictionary to my wife who was the only foreigner dining that evening, which was kindly received. Harutaka is well known for his use of rice vinegar in his shari (rice) and superior quality of neta (topping). Whilst foreigners appear to have a more divided opinion on his sushi, the locals overwhelmingly rate positively the way in which he prepares his shari. There’s a slight sharpness from the vinegar, followed by a slight saltiness, finishing with the natural sweetness of the rice.

Harutaka is well known for his use of rice vinegar in his shari (rice) and superior quality of neta (topping). Whilst foreigners appear to have a more divided opinion on his sushi, the locals overwhelmingly rate positively the way in which he prepares his shari. There’s a slight sharpness from the vinegar, followed by a slight saltiness, finishing with the natural sweetness of the rice. Appetiser – Gingko (銀杏) served slightly warm and sprinkled with salt. Certainly whet our appetite.

Appetiser – Gingko (銀杏) served slightly warm and sprinkled with salt. Certainly whet our appetite. 1st course – Japanese Tiger Prawns (kurumaebi) with Japanese radish (daikon) and ponzu. The sweet tiger prawns from Kyushu were served raw in a sashimi style and married well with the daikon and slightly sharp ponzu.

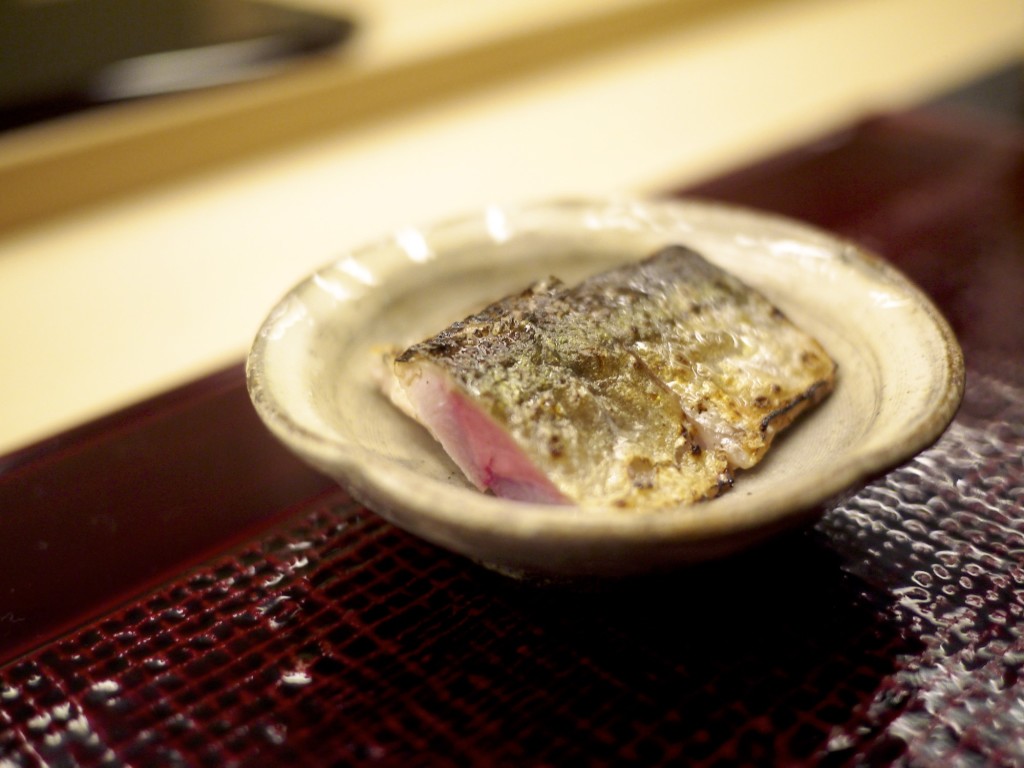

1st course – Japanese Tiger Prawns (kurumaebi) with Japanese radish (daikon) and ponzu. The sweet tiger prawns from Kyushu were served raw in a sashimi style and married well with the daikon and slightly sharp ponzu.  2nd Course – Pacific Saury / Sanma (サンマ). Slightly grilled with salt creating a lovely contrast of the crispy skin and the soft flesh of the fish.

2nd Course – Pacific Saury / Sanma (サンマ). Slightly grilled with salt creating a lovely contrast of the crispy skin and the soft flesh of the fish.  Sake – Yoemon – Junmai. A perfect timing for the arrival of my sake for the evening. It went down really well with my grilled fish at a modest price of only 3,000 yen per tokkuri.

Sake – Yoemon – Junmai. A perfect timing for the arrival of my sake for the evening. It went down really well with my grilled fish at a modest price of only 3,000 yen per tokkuri. 3rd Course – Conger pike (Hamo) with matsutake broth. The umami from the dashi used for the broth was superb and really worked well by drawing out the flavour of the delicate conger pike. There was also a slight hint of plum and vinegar which complemented the fish.

3rd Course – Conger pike (Hamo) with matsutake broth. The umami from the dashi used for the broth was superb and really worked well by drawing out the flavour of the delicate conger pike. There was also a slight hint of plum and vinegar which complemented the fish.  4th Course – Sashimi of Flounder / Hirame (平目) and slightly grilled barracuda / kamasu (梭子魚). A great combination of flavours between the sweetness of the flounder which becomes very fatty during autumn contrasted with the strong flavour the lean barracuda.

4th Course – Sashimi of Flounder / Hirame (平目) and slightly grilled barracuda / kamasu (梭子魚). A great combination of flavours between the sweetness of the flounder which becomes very fatty during autumn contrasted with the strong flavour the lean barracuda. 5th Course – Steamed abalone / mushiawabi (蒸し鮑) scorched with soy sauce. The abalone was steamed for 3.5 hours in sake before being sliced and scorched with soy sauce. It was perfect in every way with its scent, umami and crispiness. By far and beyond the best abalone my wife has ever had.

5th Course – Steamed abalone / mushiawabi (蒸し鮑) scorched with soy sauce. The abalone was steamed for 3.5 hours in sake before being sliced and scorched with soy sauce. It was perfect in every way with its scent, umami and crispiness. By far and beyond the best abalone my wife has ever had.  6th Course – Skipjack / Katsuo (鰹) with ginger soy sauce. This was our favourite course of the otsumami. There was a slight smokiness to the fish from the way in which he scorched it before dressing it with the ginger soy sauce.

6th Course – Skipjack / Katsuo (鰹) with ginger soy sauce. This was our favourite course of the otsumami. There was a slight smokiness to the fish from the way in which he scorched it before dressing it with the ginger soy sauce. 7th Course – Willow leaf fish / Shishamo (柳葉魚) sourced from Hokkaido. The flesh here was far more delicate and the flavours more subtle than others I have tasted before. Unlike the normal ones I’m use to at the typical izakayas, this one was completely absent of any bitter aftertaste.

7th Course – Willow leaf fish / Shishamo (柳葉魚) sourced from Hokkaido. The flesh here was far more delicate and the flavours more subtle than others I have tasted before. Unlike the normal ones I’m use to at the typical izakayas, this one was completely absent of any bitter aftertaste.  We looked over to see the chef preparing for the private dining room’s next few nigiris who were far ahead of us. The quality of the tuna looked very good.

We looked over to see the chef preparing for the private dining room’s next few nigiris who were far ahead of us. The quality of the tuna looked very good. 8th Course – Squid / Sumi ika (スミイカ). Our first sushi was a silky and tender ink squid. Absent of any rubbery texture, this was as good as squid goes.

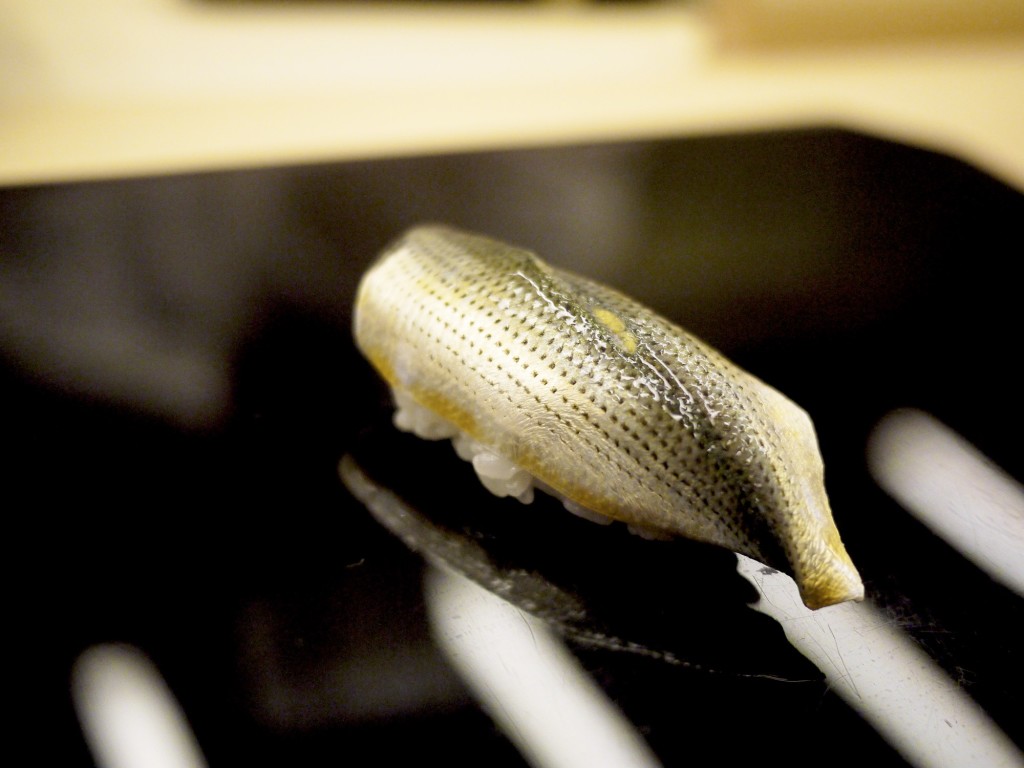

8th Course – Squid / Sumi ika (スミイカ). Our first sushi was a silky and tender ink squid. Absent of any rubbery texture, this was as good as squid goes. 9th Course – Striped Jack / Shima aji (縞鯵). An impressive sushi with an incredible sweetness and fattiness from the slightly pickled fish competing with the slightly sharp shari.

9th Course – Striped Jack / Shima aji (縞鯵). An impressive sushi with an incredible sweetness and fattiness from the slightly pickled fish competing with the slightly sharp shari.  10th Course – Lean part of the Tuna / Akami (鮪赤身). The shari actually worked best here with the tuna. Attention to detail here was important and my wife’s tea was changed just before the akami was served (it is common practice to change the tea when tuna is served to cleanse your palate between the tuna courses and bring the temperature of the tea up again).

10th Course – Lean part of the Tuna / Akami (鮪赤身). The shari actually worked best here with the tuna. Attention to detail here was important and my wife’s tea was changed just before the akami was served (it is common practice to change the tea when tuna is served to cleanse your palate between the tuna courses and bring the temperature of the tea up again). 11th Course – Medium fatty tuna / Chuutoro (鮪中トロ). An absolute masterpiece of nigiri. The sweetness and fattiness of the tuna penetrated right through the sharp and salty shari. A match made in heaven with no lingering fatty aftertaste. This was probably the best chuutoro I’ve ever had.

11th Course – Medium fatty tuna / Chuutoro (鮪中トロ). An absolute masterpiece of nigiri. The sweetness and fattiness of the tuna penetrated right through the sharp and salty shari. A match made in heaven with no lingering fatty aftertaste. This was probably the best chuutoro I’ve ever had. 12th Course – Fatty Tuna / ootoro (鮪大トロ). A lovely cut of tuna but personally I felt the combination of the medium fatty tuna and the shari was superior. Each to their own I guess! It did however allow us to appreciate the different textures and flavours of the whole fish.

12th Course – Fatty Tuna / ootoro (鮪大トロ). A lovely cut of tuna but personally I felt the combination of the medium fatty tuna and the shari was superior. Each to their own I guess! It did however allow us to appreciate the different textures and flavours of the whole fish. 13th Course – Gizzard shad / Kohada (小鰭). This nigiri required a labour of love in order to remove the distinct smell, leaving only a peasant oiliness and sweetness behind. The fish was sourced from Amakusa in Kumamoto prefecture. I was pleasantly surprised with the quality given the best season to fish is normally November / December, and we were a month early.

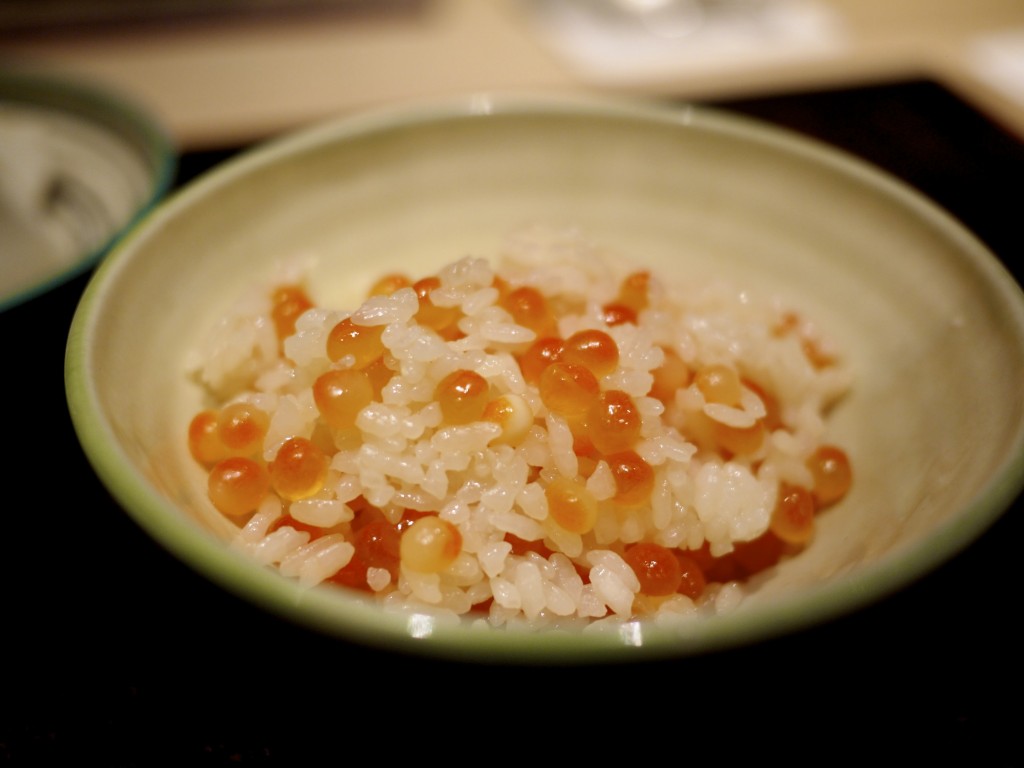

13th Course – Gizzard shad / Kohada (小鰭). This nigiri required a labour of love in order to remove the distinct smell, leaving only a peasant oiliness and sweetness behind. The fish was sourced from Amakusa in Kumamoto prefecture. I was pleasantly surprised with the quality given the best season to fish is normally November / December, and we were a month early. 14th Course – Salmon Roe / Ikura (イクラ). An all time favourite of mine since I was a kid and this certainly didn’t disappoint. The salmon roe was slightly pickled in soy sauce to enhance the flavour. Each pearl burst with a gooey delicious salty juice.

14th Course – Salmon Roe / Ikura (イクラ). An all time favourite of mine since I was a kid and this certainly didn’t disappoint. The salmon roe was slightly pickled in soy sauce to enhance the flavour. Each pearl burst with a gooey delicious salty juice.  15th Course – Japanese Pilchard / Iwashi (いわし). This nigiri was my personal favourite of the evening. The umami was incredible and it just melted in your mouth with little effort like a slice of the finest iberico ham. The slight bit of ginger underneath cut through oiliness of the fish.

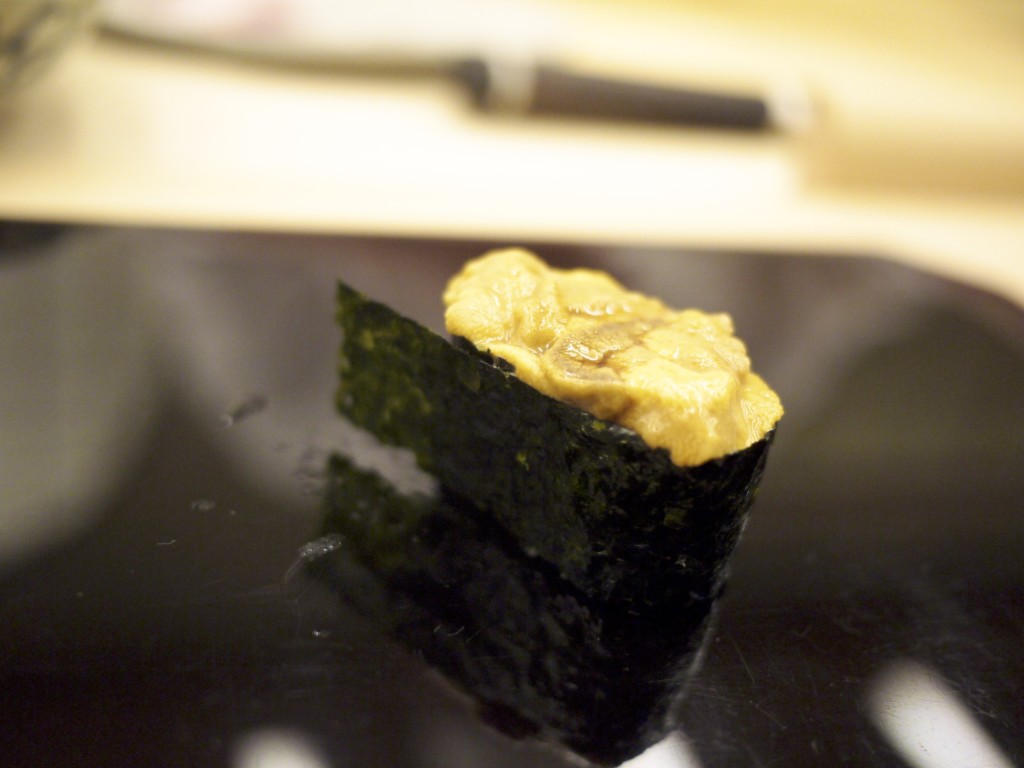

15th Course – Japanese Pilchard / Iwashi (いわし). This nigiri was my personal favourite of the evening. The umami was incredible and it just melted in your mouth with little effort like a slice of the finest iberico ham. The slight bit of ginger underneath cut through oiliness of the fish.  16th Course – Sea urchin / Uni (雲丹). A classic nigiri which required very little interference. Sourced from Hokkaido again, this was a beautifully sweet, creamy and absent of any bitter aftertaste.

16th Course – Sea urchin / Uni (雲丹). A classic nigiri which required very little interference. Sourced from Hokkaido again, this was a beautifully sweet, creamy and absent of any bitter aftertaste. 17th Course – Amberjack / Buri (鰤). Sourced from Himi at Toyama prefecture, home to one of the best amberjack in Japan. I did however find that the vinegar rice and the fish on this occasion wasn’t quite the perfect match, although the quality and preparation of the fish was second to none.

17th Course – Amberjack / Buri (鰤). Sourced from Himi at Toyama prefecture, home to one of the best amberjack in Japan. I did however find that the vinegar rice and the fish on this occasion wasn’t quite the perfect match, although the quality and preparation of the fish was second to none. Chef Harutaka spoke very little English but was happy to answer any question I translated for my wife. Whilst he was very focused in his job, meticulously preparing each nigiri, we couldn’t help but notice that he looked like he was having fun. Perhaps it was the cheerful crowd of three sitting at the other end of the counter (they appear to have been celebrities), but he certainly did not stop smiling all evening.

Chef Harutaka spoke very little English but was happy to answer any question I translated for my wife. Whilst he was very focused in his job, meticulously preparing each nigiri, we couldn’t help but notice that he looked like he was having fun. Perhaps it was the cheerful crowd of three sitting at the other end of the counter (they appear to have been celebrities), but he certainly did not stop smiling all evening. 18th Course – Red clam / Akagai (赤貝). Again the quality of the superior red clam could be tasted here even before you ate the nigiri. The olfactory senses were teased before the tastebuds picked up the natural sweetness of the clam as soon as it landed on our tongue. Sensational.

18th Course – Red clam / Akagai (赤貝). Again the quality of the superior red clam could be tasted here even before you ate the nigiri. The olfactory senses were teased before the tastebuds picked up the natural sweetness of the clam as soon as it landed on our tongue. Sensational. 19th Course – Salt water eel / Anago (穴子). A lovely finale to our sushi segment which also brought a sense of disappointment that this was over all too quickly (mind you we were there for 2.5 hours). The eel was delicate in its soft texture, yet packed with enough flavour to balance well against the shari.

19th Course – Salt water eel / Anago (穴子). A lovely finale to our sushi segment which also brought a sense of disappointment that this was over all too quickly (mind you we were there for 2.5 hours). The eel was delicate in its soft texture, yet packed with enough flavour to balance well against the shari.  20th Course – Sweet egg omelette / Tamago (玉子). The omelette here was of the the finest quality one could get, utilising grey prawns (shiba ebi) and mountain potato (yamatoimo). It was very airy inside yet also had a firmness and held a lot of moisture. They say that one must have trained for over ten years before being able to serve an omelette at Sukiyabashi. You could certainly see the skill that went into making this tamago.

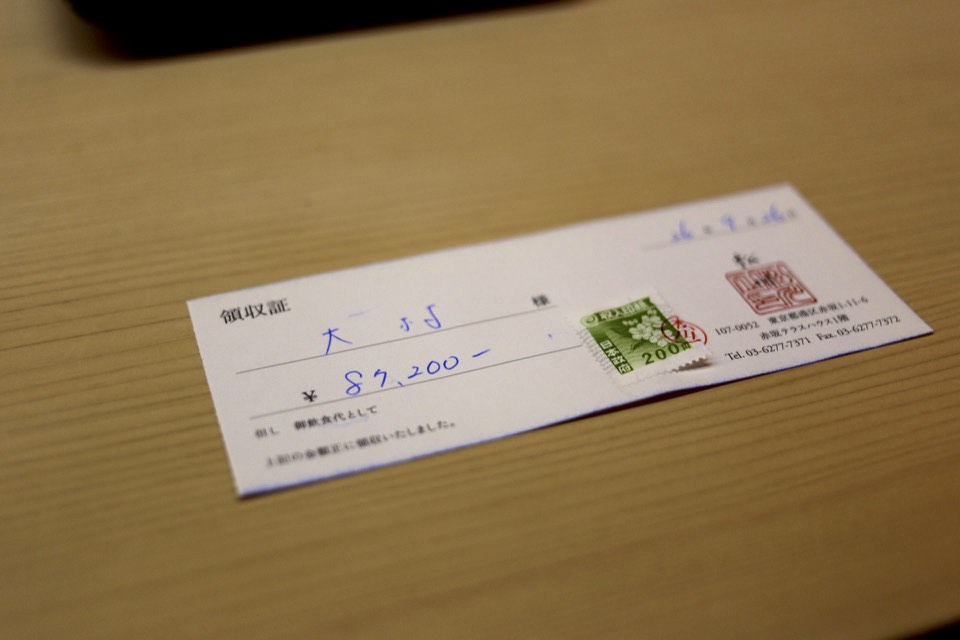

20th Course – Sweet egg omelette / Tamago (玉子). The omelette here was of the the finest quality one could get, utilising grey prawns (shiba ebi) and mountain potato (yamatoimo). It was very airy inside yet also had a firmness and held a lot of moisture. They say that one must have trained for over ten years before being able to serve an omelette at Sukiyabashi. You could certainly see the skill that went into making this tamago.  All in all the meal came to about 33,000 yen per person including the sake and a beer at the start which isn’t cheap yet certainly worth every yen when you consider the calibre of the food here. When I raised the question about the red book, the chef shrugged his shoulders as if he really couldn’t care too much. When you looked around the room you could see why. Every single diner here, other than us, appeared to be a regular and the chef knew each person’s likes and dislike. In an intimate environment like a proper sushi-ya, the regular custom is far more important than attracting new diners from afar. Whilst it makes getting reservations even more difficult for people living overseas like myself, I do hope this tradition does not disappear. It’s comforting to see that bond between a diner and a chef.

All in all the meal came to about 33,000 yen per person including the sake and a beer at the start which isn’t cheap yet certainly worth every yen when you consider the calibre of the food here. When I raised the question about the red book, the chef shrugged his shoulders as if he really couldn’t care too much. When you looked around the room you could see why. Every single diner here, other than us, appeared to be a regular and the chef knew each person’s likes and dislike. In an intimate environment like a proper sushi-ya, the regular custom is far more important than attracting new diners from afar. Whilst it makes getting reservations even more difficult for people living overseas like myself, I do hope this tradition does not disappear. It’s comforting to see that bond between a diner and a chef.